History

For many of us living in modern Ireland and Scotland, the world of Na Gaill can seem completely alien to us.

Fore ease of reading this has been broken up into concise sections.

Gaelic Society

The Norse

The Hiberno-Norse

Downfall of the Vikings and the rise of Brian Boru

Specifics of Gaelic warfare

Books, documentaries and other sources where you can read more

Before English colonisation, the island of Ireland was divided into thousands of familial clans, subject to petty kings who ruled over their kingdoms or ríochtaí. These petty kings were, in turn, vassals of the High King or Ard Rí. The Ard Rí’s seat of power was located in Tara, Co. Meath, Ireland.

The majority of the people of Ireland and the west coast of Scotland found themselves under the rule of Ard Rí Brian Ború (post Na Gaill). Many Norse peoples also made their homes in settlements such as Dublin and Limerick, living as subjects of the Ard Rí. However, Norse communities often rebelled in an attempt to exert greater control over the island.

Although the Ard Rí acted as the ruler of the land, this title was nominal as Gaelic society was decentralised in comparison to that of the English or Franks. It was this decentralisation that defeated the Norse yet led others to establish a firm foothold in Ireland during the Norman and Tudor conquests of Ireland. Native populations did not consolidate power and form a central government, thus weakening them to localised attacks and rebellions.

This however did help the Gaelic people fight back against the Vikings. Unlike in England where they defeated 2 or 3 kings and took over large swathes of the country, the Gaels had been used to fighting and raiding for millennia. The arrival of the Vikings just meant another group of men who’ll come to raid in the night which they were well used to as before the Vikings, the Gaels were the scourge of Britain raiding and kidnapping people.

Eventually through intermarriage, Hiberno-Norse ancestry was highly prized among Nordic royal families of this period. By the time of Brian Boru, many of the Gaelic and Norse figures were actually related through a web of complex political marriages.

Gaelic Society

Gaelic society differed greatly to our modern conception of the term. The land surrounding Gaelic settlements belonged largely to clans, rather than individual chieftains. Chieftains acted as representatives of clans and thus were required to be physically robust and without blemish.

Farming lands were provided to those clan members deemed competent to support the clan. Material goods produced by clan members contributed to the collective wealth of the clan. Items such as cattle, grain, wool and crops were extremely important to the material success and wealth of the clan.

This is loosely referred to as the Roinndáil system, also known as the “Rundale” system or “Booleying” in English. In a nutshell clan settlements would be clustered in a number of locations and the clan would move to these different locations throughout the year to alleviate pressure on the land in each one of these locations. Moving their cattle to their spring grounds, then to summer grounds and all around while leaving some fields to fallow. By skipping a season and not over intensely farming crops in one location they allowed nitrogen to return to the soil naturally through the growth of wild clover etc.

According to Brehon laws, of which earlier on and especially before Christianisation women could be Brehon judges, there was a Tanistry. As Gaeilge Taoiseach refers to the chieftain and Tánaiste refers to their appointed successor. Many of the males of the clan were related, marrying women from outside of the clan. Of these decedents of the Taoiseach a Righdamhna or assembly of kingly people was formed to choose the most capable one to become Tánaiste. After the Tudor Conquest of Ireland in the 17th century Tanistry was replaced with Primogeniture and English Common Law.

The Norse

789AD marked the beginning of the Viking Age, with the Lindisfarne raid taking place in this year. For many years prior to the raid, the monastery at Lindisfarne in England had become familiar with Scandinavian traders and relations were peaceful. However, the 789AD raid marked a turning point in this relationship, marking it as adversarial.

Viking ships allowed the Norse to cross the North Sea from Norway and Denmark in record time. Oak timber ships were expertly made by experienced shipbuilders. Curved planks were used to build a variety of different ships, including knarrs, snekkjas and drekkars - all of which are featured in Na Gaill. Constructing the hull of long beams of unbroken timber allowed ships to twist and turn in the water without snapping. A clinker-built hull created watertight sides and its shallow draft helped it to sail up rivers quickly. By avoiding the drag of the water, Vikings ships were able to reach speeds of 15 knots, or 28km/h.

We have evidence of this expert shipbuilding from the accounts of the Roman historian Tacitus when he described the “Suones” in 98AD. The Suones were a Germanic tribe who were called the Svear in their own language eventually moving North from Germany to Sweden. 200 years before this the Cimbri from modern day Denmark migrated south due to famines caused by a shift in the climate, by allying with another Germanic tribe called the Tuetones they together threatened Rome inflicting great defeats upon them. The Roman general Gaius Marius eventually defeated this coalition and enacted the famous “Marian Reforms” as a result. The Norse of the early medieval period are descended from these Germanic tribes among others.

In sharp contrast to the Gaels, Norse society was very individualistic. Personal glory was of the utmost importance and their pagan faith placed a strong emphasis on glorious death in battle. Where the Gaels preferred asymmetric warfare, opting for ambushes, the Norse preferred pitched battles with complex manoeuvres. However, like the Gaels, the rule of Law was very important and hefty fines were often paid for transgressions.

The Hiberno-Norse

The nimble barefoot Gaels were inspired by the heavily armed Vikings. In some cases they adopted the heavy arms of Norse settlers and many Norse settlers who settled in the isles and Ireland became what was known as the Hiberno-Norse. The Norse, being unable to overwhelm the Gaelic peoples decided to settle in key locations such as Limerick, Dublin, Cork along with Hebrides, the isle of Man, the Orkney and Shetland isles.

From there many individuals built vast trade empires, intermarrying into the Native Gaelic populations for protection and access to the lucrative trade of goods and slaves. Many Gaelic warriors in Scotland adopted heavy chainmail, large axes and strong helmets to become the Gallóglaigh or Gallowglasses. Gallowglass from the Irish “Gall Gaeil” which means “Foreign Gael” due to the extensive intermarriage of Gaels in Scotland with Norse settlers from Scandinavia.

Downfall of the Vikings and rise of Brian Boru

During Brian Boru’s lifetime the population of early medieval Europe was a fraction of what it would grow to 1000 years later. Europe wasn’t as densely populated at this time in the same way as Song dynasty China, the Indian subcontinent or even the empires of Meso-America.

Ireland at this time had a population of around 500,000, with the land divided between almost 150 petty kings. This is why the Tudor conquest of Ireland, with its systemic killings of around 200,000 people, was so devasting that its implications reverberates throughout Irish history even to the modern day. This in part was caused by the decentralised nature of Gaelic society which Brian Boru tried hard to alter throughout his long life.

Being recognised as High King in 1002, Brian Boru set out to consolidate control of Ireland from foreign influence of the Viking sea kings based in Dublin and other parts of Ireland, the Isles and the Highlands of Scotland. in the annals of Ulster he is the only Irish king in history to be described as “Ardrí Gaidhel Erenn & Gall & Bretan, August iartair tuaiscirt Eorpa uile/High King of the Gaels of Ireland and the Norse foreigners and the Celtic Britons, Augustus of all north-western Europe”. He also adopted the Latin title of “Imperator Scotorum/ Emperor of the Scots/Gaels”.

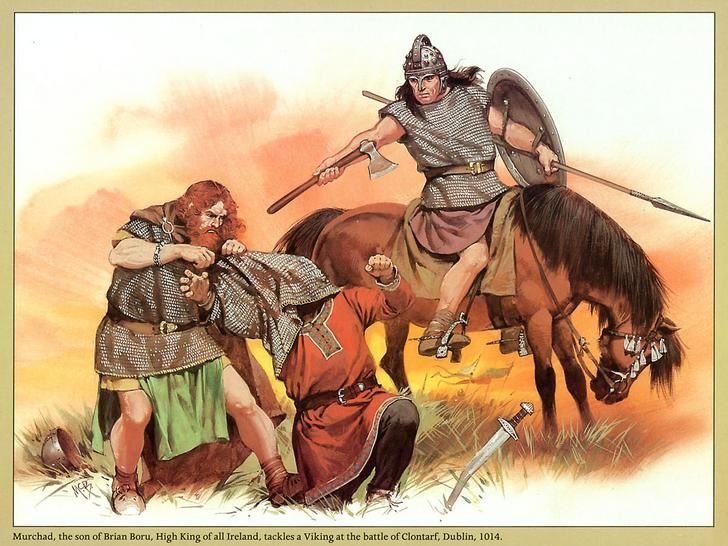

His mission ultimately failed during the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. With the battle Brian Boru’s forces successfully drove the Norse/Gaelic army of Dublin into the sea while in the process his sons were slain in the battle with himself being cut down by a stray Viking who found him praying in his tent. After Brian Borus death High Kingship returned to the Uí Néill king Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill putting an end to Brian Boru’s imperial ambitions. Eventually Viking incursions would cease entirely after the killing of Norwegian king Magnus Barefoot in Armagh in 1103 yet no other king of the Gaels would reach the heights of power that Brian Boru had at the start of the previous millennium.

Specifics of Gaelic warfare

Gaelic warfare for the most part differed greatly from the ideals of “Total War” that would be familiar to the empires of Western Europe. Warfare for those in Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland consisted more of small scale rapid skirmishes, asymmetric engagements but that’s not to say there were not pitched battles from time to time.

As Gaeilge an army is called a Slua, Slua is a vague term however and can refer to 30 or 3000. It has entered the English language as “Slew”. It’s also one of the root words in the etymology of the word “Slogan”.

The basic slua composition was as follows:

Ceithrenn Kerns/Catarans were the backbone of Gaelic armies. Lightly armed and with little to no armour. Armed with spears, bows, javelins, small axes, swords along with a long knife and a small round shield they sacrificed protection for agility and damage output. With barefeet they could move silently or tear across a grassy field at a rapid speed, ferociously hitting an enemy with everything they had before breaking away and disappearing again into the countryside. Terrifying tactics for ambushes but ultimately a handicap in large scale pitched battle.

Gallóglaigh Gallowglasses were “Foreign Gaels” of the isles of Scotland where local Gaelic people intermarried with the Norse. These warriors acted as upgraded Ceithrenn using large two-handed Dane axes, Claidheamh-mòr Claymores and wearing heavy chainmail armour yet again barefoot well up into the beginning of the 17th century. Their role as heavy infantry allowed the Ceithrenn to retreat behind their lines, reform and hit the enemies flanks while the Gallóglaigh act as tanks in the centre. Later in the medieval period many Tuatha or “Clan lordships/individual tribes” would field their own domestic Gallóglaigh and not rely on mercenaries from Scotland.

Marcach Hobelars were light cavalry used extensively by Gaelic armies. They rode small cob ponies, hardy and robust animals compared to the more delicate thoroughbred horses of Western European empires. These horses could cross terrain that was hazardous to taller horses and they could do it quickly. The men who rode these horses were basically mounted Ceithrenn and their role on the battlefield was almost exactly the same while also acting as mounted archers to harass opponents and capture routing enemies.

Ridire were the Gaelic answer to Western European Knights. Heavily armed with spears, axes and swords they relieved the Marcach in the the same way the Gallóglaigh relieved the Ceithrenn in battle allowing them to reform and attack unarmoured enemy flanks. They were significantly more heavily armoured than normal Marcach sporting chainmail and sometimes a bronze breastplate.

Schiltron During the Wars of Scottish Independence, the Schiltron was employed by the Scots against the invading English to counter their heavy cavalry and devastating longbowmen. The kingdom of Scotland was a mosaic of Gaelic Highlanders, Norse islanders, Doric Aberdonians and Saxon Northumbrians from everywhere south of Stirling. This being said, Schiltron tactics evolved with the introduction of gunpowder, were modified and began to be employed by Gaelic armies being influenced by the Spanish Tercios supported by advanced Ceithrenn adopting Spanish Rodelero tactics. This consisted of basically Pike and Shot where arquebusiers (proto musketmen) were protected from cavalry charges by long pikes and those pikes were protected from advancing infantry by sword and shield infantry withing the ranks of the Pike and Shot square.

Píobaire Bagpipes were an important part of later Gaelic armies. In the 13th century they replaced the traditional horns and trumpets of previous Gaelic armies as Pipes were brought to Europe from the Middle East during the crusades. The bagpipe as we know it today was purely an instrument of war and was banned after the English conquest of Ireland.

Where can I learn more?

There are many books and documentaries out there for you to learn more about this subject.

Here’s the list:

Early medieval Ireland, 400-1200 by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín

A New History of Ireland, Vol. 1: Prehistoric and Early Ireland - edited by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín

University College Cork's CELT Project

"What is the Golden Age of Ireland?" - Irish Medieval History on YouTube

"Columba & Ireland's Golden Age" - HistoryTime on YouTube

Íospartaigh na Lochlannach - TG4 (Victims of the Scandinavians - TG4)

Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia - Seán Duffy

The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600 - Seán Duffy

Warfare in Twelfth-Century Ireland - Marie Therese Flanagan

Rural settlement and cultural identity in Gaelic Ireland - Tadhg O’Keefe